Case Status: Victory. University settled on terms favorable to student.

Hinkle v. Baker

Steven Hinkle goes to court to challenge one-sided use of student conduct code

In 2003, CIR represented Steven Hinkle, a student at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo, who was dragged before a school tribunal and threatened with expulsion solely for exercising his right to free speech by advertising an upcoming lecture in the student lounge area.

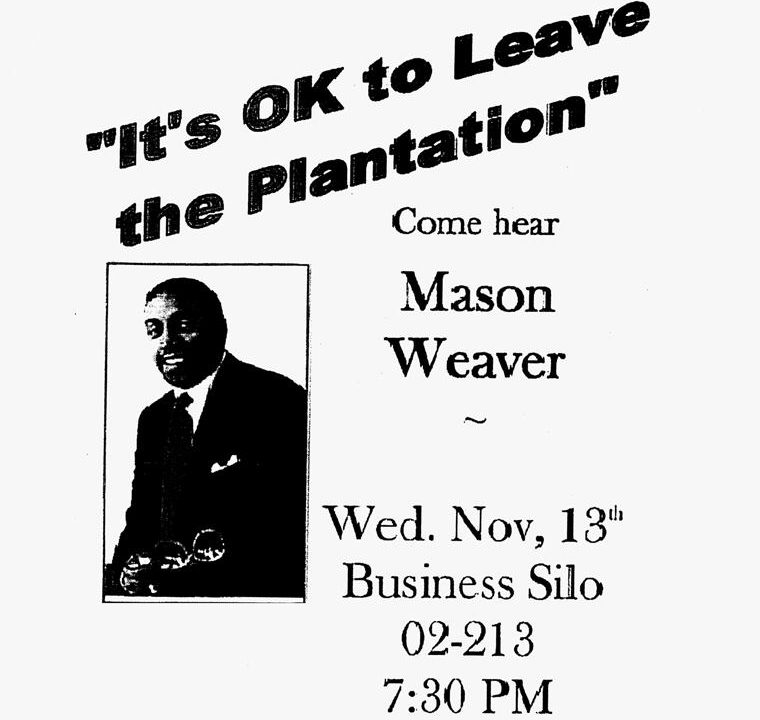

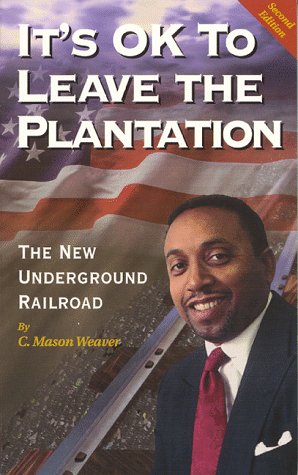

Hinkle’s problems began on November 12, 2002, while he was posting fliers around the campus of Cal Poly. The fliers advertised a lecture the next evening by author Mason Weaver. Weaver was to talk about his book, It’s OK to Leave the Plantation: the New Underground Railroad. In the book, Weaver argues that dependence on government programs puts many African Americans in a situation similar to slavery.

When Hinkle attempted to post the flier on a public bulletin board located in a student lounge area in the Multicultural Center, he was approached by several African-American students who claimed to be holding a bible study meeting nearby. Though the flier listed only Weaver’s name, the title of his book, and the time and place of the lecture, the students told Hinkle the announcement was “offensive.” They asked Hinkle not to post the flier and said they would call the police if he didn’t leave.

After briefly trying to discuss the students’ comments with them, Hinkle left the lounge without posting the flier. Nonetheless, one of the students called the campus police to complain. The police arrived immediately and reported that they had been “dispatched to the multi-cultural center to investigate a suspicious white male passing out literature of an offensive racial nature.”

Hinkle is charged with disruption

Hinkle was summoned to meet with school officials. They told him that the lecture announcement was offensive to the African-American students in the lounge. One administrator suggested that his being white and having blond hair and blue eyes was a “flashpoint.” On January 29, 2003, Hinkle was formally charged with “disruption” of a “campus event” — the purported bible study meeting — in violation of California Code of Regulations, Title 5, Section 41301(d). (In fact, when Hinkle entered the study lounge, there was nothing to indicate that a meeting or bible study was taking place. No meeting notice, Bibles, or praying could be seen, and pizza was being eaten.)

As a result of the charges, Hinkle was subjected to a seven-hour judicial hearing on February 19. Several weeks later, Hinkle received a letter from Vice Provost David Conn conceding that there was “no evidence that you entered the Multicultural Center with intent to disrupt the Bible Study.” Nonetheless, the letter told him his flier had disrupted the meeting and ordered him to write a “formal letter of apology” to the complaining students to be approved by the Office of Judicial Affairs. An accompanying document from Judicial Affairs warned Hinkle that if he did not accept this punishment, he would face much stiffer penalties, up to expulsion. Read an abridged or full version of the 7-hour hearing transcript.

Although Hinkle was convicted of “disruption,” Cal Poly officials and the complaining students made it clear that the problem was not any physical interruption of the purported meeting. (In fact, it was the students in the lounge who initiated the exchange with Hinkle and called in the police.) Instead, officials point to the allegedly offensive nature of the lecture announcement and the distraction caused by the students’ reaction to it. For example, the student who called the police, said the flier was “hate speech against us.” And Cal Poly’s Director of Judicial Affairs questioned how Hinkle “could have a poster like that and walk into a room full of African-American students and not think that there might be people who would find that offensive.” Read UPI’s account of the facts of this case.

Hinkle was punished for the content of his expression — which is constitutionally protected — rather than for disruptive conduct. It was clear that the charge of disruption is simply a pretext for punishing Hinkle for his point of view. Posting a flier on a public bulletin board announcing a talk on a topic of public importance is at the heart of the First Amendment. The school could not punish Hinkle simply because students found the topic controversial. More generally, the Hinkle “episode provides a window into the politically correct censorship that pollutes so many of our nation’s campuses.” Stuart Taylor in his column in the July 14, 2003 issue of National Journal.

CIR defends Hinkle’s First Amendment rights

Hinkle cited his First Amendment right to free speech throughout the disciplinary proceedings and refused to apologize. “Censorship runs in direct opposition to the very purpose of academic institutions like Cal Poly. That’s why this is so shocking,” Hinkle told the FOX News Channel’s Hannity & Colmes.

Hinkle first sought help in defending his rights from the Philadelphia-based Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), which sent two letters to Cal Poly President Warren Baker reminding him that Hinkle’s posting of the flier was protected by the First Amendment. Nonetheless, the conviction remained in Hinkle’s permanent school record and the threat of future censorship and punishment hung over his head. Realizing that legal action was necessary, FIRE referred the case to CIR and co-counsel Carol Sobel, a private practitioner and former ACLU attorney in Santa Monica, California.

On September 25, 2003, CIR and Sobel filed a lawsuit on Hinkle’s behalf in federal district court in Los Angeles. The attorneys also requested a temporary restraining order for immediate protection of Hinkle’s First Amendment rights. Named as defendants in the lawsuit, were Cal Poly officials, including President Warren Baker.

The complaint asked the court to declare that the University’s ban on “disruption” was unconstitutionally vague and overbroad. Hinkle also sought an injunction prohibiting Cal Poly from disciplining him for the flier incident and from banning or punishing “disruptive” speech or expression in the future. The requested injunction ordered the University to expunge the allegations and conviction from Hinkle’s school records. In addition, Hinkle sought compensatory and punitive damages.

In another victory for CIR, California Polytechnic State University agreed that it was improper to punish a student solely on the grounds that other students found his speech to be controversial. The school agreed to clear Steve’s student record, let him post fliers in the future, and pay $40,000 in legal fees.

CIR’s free speech victories in the federal courts have made it harder for school officials to censure students and professors merely because someone finds their viewpoint offensive. The Hinkle case was important in establishing the principle that such disruption must be based on an objective and reasonable standard. Absent that principle, school officials and hypersensitive identity groups could veto the constitutionally protected speech of others.